Has any great filmmaker left as chaotic a legacy as Orson Welles? The director of Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons and Touch of Evil spent the last years of his life working on several projects, none of which he finished to his satisfaction. On the day of his death on October 10, 1985, he was preparing scenes for a television special, Orson Welles’ Magic Show.

Welles bequeathed his unfinished materials to his companion Oja Kodar, who in turn donated most of them to the Munich Film Museum. Stefan Drößler, an archivist and the current director of the museum, will be introducing some of Welles’ work as part of the Museum of Modern Art’s “To Save and Project” festival.

Drößler’s program includes The Merchant of Venice (1969) and King Lear (1985), both on November 19; scenes from The Other Side of the Wind (1970–76) and The Dreamers (1982) on November 20; a new version of Journey into Fear (1943), November 21; and a work print of The Deep (1967) on November 22.

These films are not generally available to the public, and perhaps may never get commercially released. So grab the chance to see them if you can.

During his lifetime, Welles was plagued with setbacks and obstacles, from funding problems to, as in the case of It’s All True and The Deep, the death of one of his actors. In the years since his passing, the difficulties have multiplied.

“The problem is, the moment the name of Orson Welles comes up, there are always people who believe they can make money with it,” Drößler says. “There are always some legal problems that have to be solved on these productions. Welles took money from different sources, people claimed to have rights, quite often there aren’t contracts for everybody who was involved on a project. His work is always more difficult than any other film I’ve worked on. Unfortunately, before you invest an enormous amount of money in one of these restorations, you have to clear the bases.”

Drößler faces ongoing preservation issues with the Welles collection, which includes 16mm, 35mm, and video elements. Color fading is the worst problem, surprisingly more pronounced on 35mm stock than 16mm. Materials for The Merchant of Venice had faded to magenta, and required intensive digital processing.

“Some of the projects from the late sixties are in high danger,” Drößler said. “The Deep is losing color just like The Merchant of Venice. We did a transfer, corrected the color a little in a work print, but it needs a very expensive, high-quality treatment very soon.”

Welles spent three years shooting The Deep, his adaptation of the Charles Williams novel Dead Calm. He also acted in it opposite Jeanne Moreau and Laurence Harvey. Some scenes were never filmed, and when Harvey died in 1973, Welles was effectively prevented from completing the movie.

However, two work prints, one in black-and-white, survive. In them, Welles assembled the shots he wanted, sometimes several takes in a row, and then started editing scenes. “He even put in blank film for missing shots to be filmed later,” Drößler said. “We combined the two work prints, but there are missing scenes I have to explain during the presentation. And of course it is much too long, 111 minutes. Welles wanted it to be a short thriller of maybe 80 minutes. Also, the music is missing, which for a suspense film is quite important.”

Drößler has shown the work print at conferences, and admits he was disappointed by its reception. Some Welles experts complained that The Deep was a minor film, that it started well and then became boring.

“You have to use your imagination to see the possibilities in the material,” he insists. “Think of it as Orson Welles would cut it.”

Long considered unfinished, The Merchant of Venice is a condensation of the Shakespeare play Welles intended to use in a television special for CBS called Orson Welles’ Bag. Roughly half an hour, Welles’ version dispenses with Portia. The director plays Shylock. He screened the completed version for Oja Kodar and her mother, but afterwards two of the three reels were stolen.

The negative survived, but without sound. Drößler despaired of restoring the film until additional material surfaced in Italy.

“I finally found the original script, and notes from composer Francesco Lavagnino, who had already recorded the score. Also his notes had an exact continuity of the scenes. But we still didn’t have the sound for the second half.”

Drößler hired lip readers to correlate the actors on film to lines in the script, “but of course Orson didn’t always follow the script. We could use intertitles, but there was just too much dialogue. We could try a new dub, but you can’t dub Orson Welles without losing a lot of impact.”

But Drößler discovered that while Welles would tamper with the order of lines and scenes, he never changed Shakespeare’s actual lines. With some digital help, Drößler could dub Welles’ 1978 voice recording of The Merchant of Venice onto his 1969 film.

“It’s not the ideal solution, but it’s the best solution possible in this situation,” Drößler says.

For The Dreamers, an adaptation of two Isak Dinesen short stories, Drößler will be showing the test scenes Welles shot with Kodar. Welles worked for six years on The Other Side of the Wind, starring John Huston and Peter Bogdanovich, who announced in 2014 that he would complete the film with producer Frank Marshall. Their crowdfunding campaign on Indiegogo failed to reach its goal of $2 million (later reduced to $1 million).

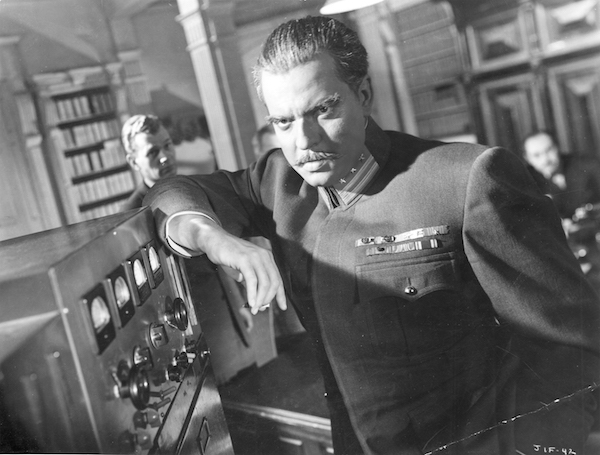

The novel Journey into Fear helped established author Eric Ambler’s reputation as a suspense writer on a par with Graham Greene. Welles saw the book as a sort of respite after Kane and Ambersons, a light entertainment that would feature some of his Mercury Theatre friends. Although Norman Foster was the nominal director, Journey into Fear features many of Welles’ characteristic flourishes, such as deep-focus, off-kilter compositions and editing keyed to rapid dialogue.

According to Drößler, RKO removed some twenty minutes of material before releasing the film in the summer of 1942. When Welles returned to Los Angeles from Brazil after abandoning It’s All True, he was allowed to edit Journey into Fear and reshoot its final scene. Since he wasn’t allowed to make the movie any longer, he had to cut other material to keep the running time to roughly 70 minutes.

Drößler matched the one surviving print of his first edit to the cutting continuity from the preview version. Now Journey into Fear is roughly six minutes longer. “Still some scenes are missing, so we put in a title card, but now the film changes its character a little bit,” Drößler notes. “Different characters in the story line, some scenes are more explicit, lots of little pieces that help develop characters. I personally think it’s more entertaining.”

Will more Welles material show up? “It’s always possible,” Drößler says, laughing. “We don’t even know what he filmed. There’s always commercials, these strange appearances on television shows that nobody knows about. So something may pop up.”

The tangled claims on Welles’ movie may never be satisfactorily resolved, which means that some of his work may never be seen. But in Drößler’s opinion it’s just as important protect Welles as it is to release everything he did.

“For example, we have hours of material of his magic show,” he says. “Rushes, over and over, unedited. It’s the responsibility of the curator to sort this material, find a solution, a way to present it to the public.

“A bad reconstruction can destroy your belief in a film, the myth of a film. Don Quixote was always thought to be one of Welles’ great projects, but there was a reconstruction that wasn’t very well done, and now the reputation of the film has been heavily diminished.”

The complete schedule is available at MoMA.org/visit/calendar/films/1623.